At the beginning of the 19th century Hoar Oak Cottage appears to have belonged to the Vellacott family who owned several properties in and around Furzehill and Barbrook, near Lynton including several hundreds of acres of moorland hills and small buildings – most probably shepherd’s huts at Folly, Benjamy and Hoar Oak. When the Royal Forest of Exmoor was sold, in 1816, a survey and allotment document was drawn up which delineated the rights of landowners around the edge of the Royal Forest. The land owned by the Vellacotts and their rights to its use are included in both the document and map which was drawn up by the Crown Commissioners. The Vellacotts had two allotments one of which appears to include the land around Hoar Oak Cottage although further researches are underway to confirm this detail. The surveyors who drew up the documents were clearly challenged with how to demarcate, in words and through maps, the remote and wild areas around Hoar Oak Cottage making the Award document an equally challenging one to read. More to come on the Crown Commissioners survey and allotment awards.

Elsewhere, other records are very clear and show that by the early 1800s a branch of the Vellacott family – Charles and Elisabeth Vellacott – was living and working and raising children at Hoar Oak Cottage. The Tithe Map, drawn up in 1836 also clearly identifies the Vellacotts as owners of Hoar Oak Cottage and many acres all around it. The names of the individual fields, as well as their acreage and tithe value is recorded and more can be read about the Tithe Map and what it tells us about Hoar Oak Cottage on this link.

Although Charles and Elisabeth Vellacott left Hoar Oak it was lived in by a succession of families, most of whom were either relatives of, or employees of, the Vellacotts. These families included Dovells, Rawles, Richards, Saunders, Lanceys, Bales and Moule and their stories – at least what has been found out to date – can be found on this link.

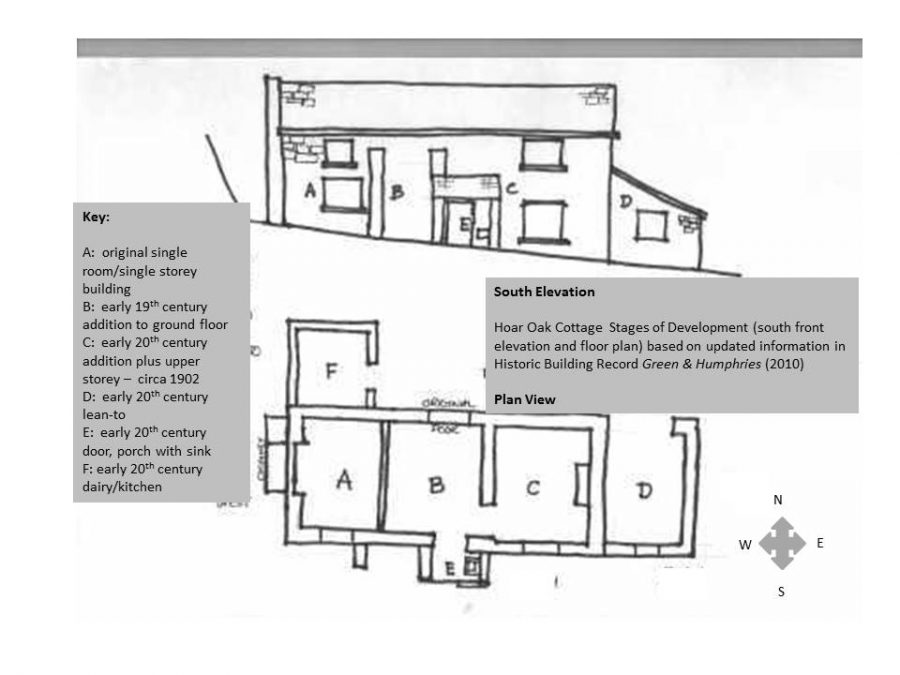

During this period the cottage was extended outwards and upwards and outside there were farm outbuildings added in order to house the family’s cows and ponies as well as the equipment and paraphernalia needed to run a remote sheep herding. As the sketch below ( based on the Green & Humphries (2010) Historic Building Record Report) shows, the cottage grew sideways and upwards during the early part of the 1800s in order – it would seem – to provide more suitable permanent accommodation for a shepherd and his family.

There has never been a road to Hoar Oak and getting building materials out across the moor is a challenge, especially when horse and cart were the main form of transport. The men responsible for the building work needed to be inventive, making use of materials easy to transport or that were easily to hand. Stones came from small, local quarries; slate was also extracted locally; timber was gleaned from nearby copses and the soil around the cottage used for mortar with the addition of precious, costly and imported lime. Door and window openings were constructed using a variety of materials and the photos below show the range of creativity employed. On the left, red bricks and local stone form a window opening and a piece of slate serves as the lintel. In the middle is a close up of the upper right hand corner of the same window where wood, slates and terracotta tiles have been cemented together to form the opening. And on the right, the window opening is formed entirely out of local stone and a piece of wood, probably beech, used for the lintel.

The sale of the Royal Forest of Exmoor, described above, took place in 1816 when the Crown sold the land to John Knight – he paid £50,000 for 16,000 acres – and this wealthy Midland’s industrialist set out to enclose, reclaim and develop Exmoor. John Knight retired in 1841 and his son, Frederic Wynn Knight, introduced a new innovation – building sheep farms up on the Exmoor hills and importing hardy Scottish sheep and employing Scottish shepherds to live and work the farms. His economic aim was to have sheep running all year round on the highest parts of Exmoor, producing one good crop of lambs a year and one good clip of wool a year and he imported over 5000 sheep and at least 20 Scottish shepherds made the journey to Exmoor.

More of the story of the Scottish Shepherds on Exmoor can be found on this link.

More of the Knight’s story can be read in The Reclamation of Exmoor Forest by Orwin and Sellick and the Archaeology of Hill Farming on Exmoor by Cain Hegarty. Frederic Knight also investigated breathing life into the many abandoned iron mines found scattered across Exmoor – one of which lay just to the south of Hoar Oak Cottage. You can read more of this intriguing story which must have been watched with interest by our Hoar Oak residents on this link.

Although Frederic Knight never owned Hoar Oak Cottage he did lease it during this period in order to house the Scottish shepherds he employed to be responsible for his Hoar Oak herding. Between 1870 and 1910 the cottage was occupied by the Davidsons and Renwicks, Johnstones and Jacksons – all shepherds from Scotland who had travelled to Exmoor to live and work at Hoar Oak.

As a consequence of the ambitions of the Knight family for reclaiming and improving Exmoor, including the expansion of sheep farming on the moorland hills, the cottage at Hoar Oak became a working farmstead and family home. More on this link.