For his many new sheep farms on the hills of Exmoor, Frederic Knight favoured the Cheviot and Blackfaced sheep. They came from sheep farms and sheep breeders in the Scottish Border counties of Ayrshire, Lanarkshire, Peebleshire and Dumfrieshire – areas renowned for their sheep farming and sheep breeding traditions. Knight imported over 5,000 sheep and brought more than 20 Scottish shepherds and their families to Exmoor. More on this link.

They implemented a style of sheep farming called ‘hefting’ which relied on the natural instinct of hill sheep to stick to their own boundaries – an instinct encouraged through breeding and management practices. “Hefted” sheep live on their own part of hills or mountains and ‘know’ where they belong – no need for fences. Every day the flock is driven from the bottom of the hills to the tops of the hills where they are left to graze their way back down during the day. In the evening the shepherd brings the flock together at the bottom of the hill, gathers in stragglers and does a quick ‘count’ checking for missing, sick or injured animals. A ‘heft’ that works well contains around 400 ewes, as this “sheepy knowledge” of the herding boundaries is the knowledge of the ewes – which they in turn pass on to their lambs. (Reference: Phillip Walling (2014) Counting Sheep: A celebration of the pastoral heritage of Britain)

Knight’s new sheep farms became populated with humans and sheep and the remote hills of Exmoor must have been noisier and busier than they had ever been, including at Hoar Oak Cottage. We have learnt much about the sheepfarming and the shepherds during this period thanks to the diaries kept by Head Shepherd – Robert Tait Little from Dumfrieshire. More about the fascinating story of Robert, his wife, family and the story that his diaries can tell can be found on this link.

What was Hoar Oak Cottage like at this time?

The cottage stayed as a one down, two up structure during the time that Frederic Knight leased the cottage – it never had a road put in to it, water came from a nearby spring, there was no electricity, all cooking was on the open fire and in the breadoven and sanitation was limited to a plank with holes erected over the river or the ‘bucket and chuckit’ system. But as the 19th century came to a close Frederic Knight sold his Exmoor Estate to the Fortescue family – a longstanding Devon family – and they maintained their interest in the Exmoor hill farms and sheepfarming.

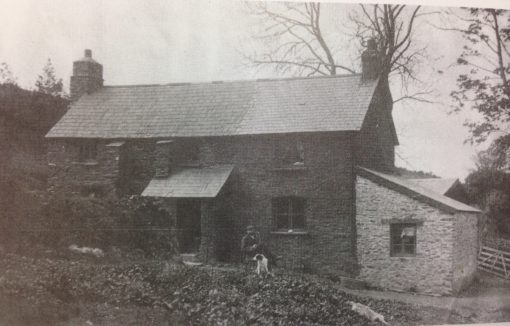

As the 20th century dawned, the family at Hoar Oak Cottage – which included 12 children – had outgrown the cottage and the Fortescues had it extended. The photo below shows the extended cottage with a new lean-to on the side.

The extension was built by George Lethaby. It appears the work was done during December 1900 and spring 1901 – a cold and difficult time of year to be undertaking building work up on the high hills of Exmoor. Between 25th January 1900 and 18th April 1901 George Lethaby submitted at least 6 invoices to the Fortescue Estate’s Land Agent for payment. The amounts range from £5 to £8 and the total cost seems to have been in the region of £32. (Thanks to Graham Wills who shared this information from his researches into the Fortescue papers held at the Devon Records Office.)

It is unclear when the extensive outbuildings to the rear of Hoar Oak Cottage were built but it may have been around the same time. These would have provided shelter and storage space for a cow or two, the pony, animal feed, peat etc.

The Fortescues continued to employ the shepherds of Hoar Oak Cottage right up until 1959 when they sold off much of their Exmoor estate. The last shepherd families were the Bass family, the Littles, Hobbs and the Antells. During this first half of the 20th century, the children carried on working on the farm but were taken, by pony, into school at Barbrook or at Simonsbath. The shepherds still worked single handed caring for their flocks but coming together to share tasks such as shearing and getting lambs ready for market. Their wives still washed clothes in the river but a new innovation – a cast iron range – was introduced and the old kitchen fireplace and breadoven disappeared. Attempts were made to till the allotment and grow feed for the sheep and the Exmoor ponies still played a key role in the day to day work and comings and goings of the families.

Memories of what Hoar Oak Cottage was like.

The 1940s saw the farm lived in by Abe Antell, the last of the Hoar Oak shepherds and his wife Gert. One of the family, Phyllis Tossell remembers going to the cottage for Sunday lunch and also in summer holidays, and vividly recalls what the house looked like at the time:

• The main entrance door was on the north side of the cottage – facing the path up to Furzehill

• There was a big wooden table with forms (bench seats) in the kitchen

• The floor was laid with uneven stone flags

• There was at least one – maybe only one – big wooden chair in the kitchen which Phyllis remembers as being where her Uncle Abe would sit

• There was the big black stove in the kitchen fireplace with a breadoven in the fireplace wall. (Note: until the ruins of the cottage were stabilised this could still be seen at Hoar Oak Cottage. It has the date 1944 stamped on it so was probably put in when the Antells lived there.)

• Off of the kitchen was an entrance into another little lean-to room – Phyllis thought it was called something like the ‘cold room’ but knew that it was where her Auntie Gert stored food, butter and milk etc.

• From the kitchen there were a few stairs down into the parlour or sitting room

• Walking down those stairs there was another door on the right (south side of the cottage) which had a little space with a porch around it and held a sink

• The stairs to the top floor may have gone up through the middle of the cottage from this passageway between the kitchen and the parlour/sitting room but our informant wasn’t sure if her memory was accurate on that one!

• The parlour/sitting room had a fireplace but it looked as though it was rarely lit

• There were some comfortable chairs in the sitting room and Auntie Gert offered the children to go in there after lunch, but they were none too keen as the furniture was quite damp and a bit green with mould.

But ‘progress was coming, it did not pass by’ and once more things were about to change on Exmoor with irrevocable consequences for the cottage. More on this link.