There has been sheep on Exmoor since time immemorial and, for probably just as long, a community of shepherds looking after them. The earliest shepherds were in the Hoar Oak valley with sheep brought from lowland farms for the rich summer grass on the high moor. Their days would have been spent outdoors, their nights in the small shepherds cott at Hoar Oak, surrounded by the same sights and sounds as can be seen and heard today at Hoar Oak – wind and river, sheep and birds, wild ponies and deer. The shepherd might be lonely but never isolated as there were many such shepherds scattered across the moor over the summer – capable and independent men for whom a walk or pony ride of several miles across the moor was commonplace.

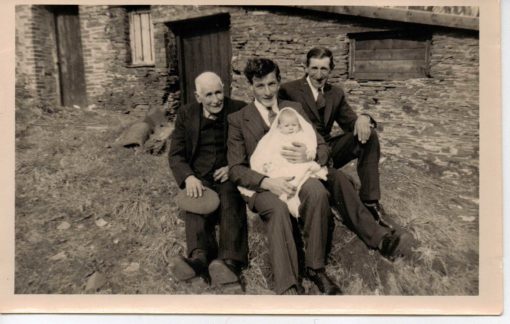

These temporary Hoar Oak shepherds, as well as the first permanent shepherds who later lived at Hoar Oak Cottage, would have had strong links to the farms and families around the northwest edge of the Royal Forest of Exmoor – farms such as Furzehill, Sparhanger, Ilkerton and small hamlets like Barbrook, Parracombe and Challacombe, families such as the Hobbs, Bowdens, Lethabys and in particular, the Vellacott family who owned Hoar Oak Cottage during the 18th and 19th centuries. Shepherding was a family tradition with son following father following grandfather.

Later, when John Knight had purchased the Royal Forest of Exmoor and his son Frederic had begun his sheep farming enterprise, they leased land in the Hoar Oak valley and the cottage which became home to shepherds from Scotland. From the mid-1800s, the Knights imported sheep and shepherds from the Scottish Borders to occupy and run many of the remotest Exmoor herdings including, for example, those at Badgworthy, Pinkworthy (Pinkery), Toms Hill, Larkbarrow and Wheal Eliza. A new Scottish community formed with its own traditions around sheep farming as well as introducing ceilidhs, Hogamany and enjoying a ‘wee dram.’ The women supported each other, as they do in any migrant community, and Simonsbath became the village focus. The men introduced the Blackface sheep and shepherding techniques similar to those used on the remote Borders hills farms. Echoes of that community can be heard from Edna Stevens – a descendant of one of the Johnstone shepherd family – who recalled:

“They all sang the old songs and did Scottish dancing. ‘Can you imagine the impact they made? All the Scottish shepherd families getting together at Simosnbath. Scottish yarns, the “highfling”, the poetry of Robbie Burns all helped by a wee drap of whisky! At the end of the party they rode home on horseback in the moonlight, the horses knew where the bogs were.”

Richard Jefferies, the author of Red Deer (1884) also remembered the impact of the Scottish shepherds on Exmoor. He writes:

“The farmhouses are now occupied by Scotch (sic) shepherds; if you knock at the door a Scotch face appears, and you are offered a glass of milk, to which you are “varra” welcome. The boundless heather, the deep glens, and the red deer correspond to the Gaelic accent.”

At the end of the 19th century, the Knight family sold their Exmoor Estate to the Fortescues, an established Devon family. For some years to come, the Fortescues retained many of the Scottish shepherd families in their employment thus making their integration into the Exmoor community complete. The Fortescues formally brought the Hoar Oak herding into their estate by purchasing the land and cottage and keeping on the Johnstone family from Lanarkshire to run it. The photograph below shows many of the Scottish shepherds and on the right Lady Fortescue – a group photo taken at shearing time c1905.

As the 20th century rolled on, just as elsewhere in the country, there was an increased movement of people and more people than ever were living and working in and around Exmoor. The Hoar Oak families were becoming integrated into an increasingly established community centered around villages with churches and chapels, schools, hospitals and improved transport by road and rail. The Victorian tourists had discovered North Devon, bringing new and different job opportunities, and two world wars served to bring the community closer. Delivery vans now called regularly at local farms and the Hoar Oak residents could leave an order for food or clothing or books or boots at a nearby farm one week and pick it up the next week – perhaps driving their pony and trap across the moor to do so. The children joined into this new community through their attendance at local schools. They were taken by pony across the moor to stay during the week with an aunt or grandmother in order to attend the school in the villages of Barbrook, Brendon or Simonsbath.

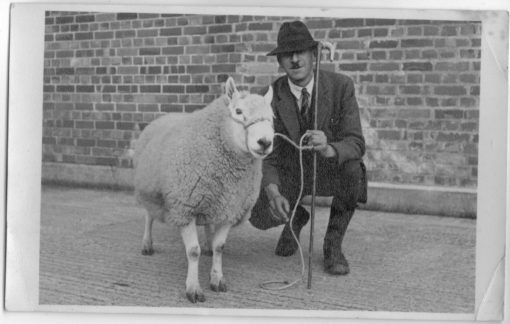

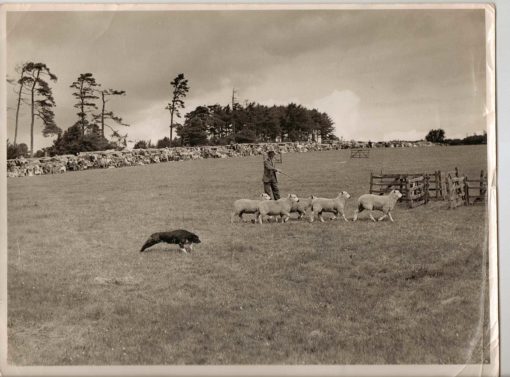

The Exmoor shepherds’ community was focused around all things sheep – not only when they got together to help each other at shearing time and at lambing time for example – but also at markets, county shows, stock fairs and at sheepdog trials where many were successful winners. One non-sheep activity shared by the community would be the annual round-up of the Exmoor wild ponies. (More to come.)

The Exmoor shepherds also had a strong commitment to supporting the RNLI. Perhaps the memory was strong of the extrodinary feat of endurance when, in 1899, the men of Lynton hauled the large, heavy, wooden lifeboat all the way to Porlock to launch a successful rescue of a boat in trouble on the Bristol Channel. Now commonly known as the “Overland Launch” this feat of endurance and bravery is captured extensively in film, photos and the written word. It is still remembered in the local area and in the early 20th century the local shepherds, including Bill Little from Hoar Oak Cottage, actively raised money for the RNLI and every year were, as a thank you, taken for an outing on the local RNLI launch in Lynmouth. The photo below shows the group being taken out sometime in the 1940s or 1950s. In the front left, smoking a pipe, in suit and hat is Shepherd Bill Little from Hoar Oak Cottage.

Although no one has lived at Hoar Oak Cottage since the 1960s there has grown up around it a community of people with fond memories of their family associations with the cottage as well as many other people from further afield who are interested in this remote spot and the stories it has to share. The Hoar Oak Cottage community is now a global one stretching out from North Devon, throughout Great Britain and farther afield to Australia and New Zealand, South Africa, the United States of America and Canada. It is a community kept together by the simple ties of people getting together, walking and talking together, as well as through the modern ties of social media.