Updated May 2024

James Maxwell Johnstone was born in 1852 in Crawfordjohn near Muirkirk, South Lanarkshire. He came from a long line of Scottish shepherds who had lived and worked for millennia in and around Crawfordjohn. In 1870, he moved with his parents to Betws Garmon in North Wales where the family were employed to run a combined sheep farm and slate quarry called Y Garreg Fawr.

Sarah Thomason was born on the 15th March, 1863 in Llanberis, North Wales. Her father, Samuel Thomason, was a quarryman who had travelled from Lancashire to Gloucestershire for work and where he married local girl Ellen Hayward (or possibly Roberts). After the birth of their first two children in Gloucestershire, the couple travelled to North Wales where Samuel had acquired work in the slate quarries, including Hafod-Y-Wern near Betws Garmon. They had 11 children including Sarah, who as a teenager, worked locally as a housemaid and met James Maxwell Johnstone through another housemaid – James’s sister. (For 9 of the Thomason children Ellen gave her maiden name as Hayward. For Sarah & George she gave her name as Roberts. To date, no reason for this has been discovered.)

James Johnstone and Sarah Thomason married in Betws Garmon in 1881 and soon after moved to live and work in Keswick in Cumbria where two daughters, Marion and Emily, were born. In 1884, James and Sarah and their two girls moved to Scotland – near the Johnstone’s home patch – most probably following the chance of work for James. They lived at Templelands, near Muirkirk, where a son Samuel was born in 1885.

In 1886, the family moved south to Exmoor to take up the Hoar Oak herding and live at Hoar Oak Cottage as employees of Frederic Knight. How that move came about is not known but it was an era of agricultural labourers needing to move about to find work. In addition, James Johnstone was related to the two previous Hoar Oak shepherds, William Davidson and John Renwick and so possibly may have heard of the job/been recommended for the job as shepherd on the Hoar Oak herding. Note: The Knights famously favoured Scottish sheep and Scottish shepherds to run their Exmoor herdings. More on this link

James and Sarah had ten more children during their time at Hoar Oak Cottage and their family of thirteen children must count as one of the ‘longest’ of what historians now call ‘long families’ of 10 or more children. The family tree below shows the children and, where known or applicable, who they married.

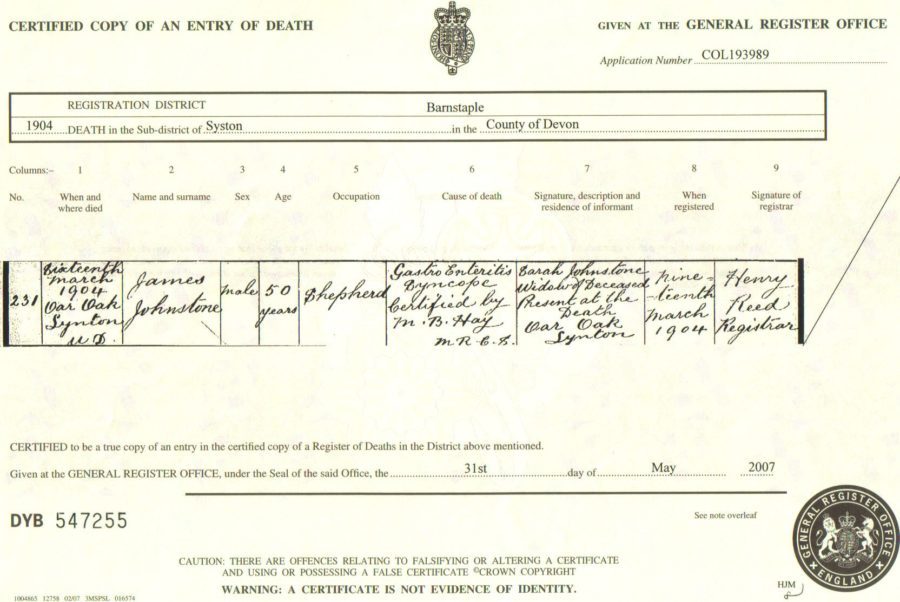

Just 10 months after the 13th child Agnes was born, James died on the 16th March, 1904. He was 52 and the cause of death is recorded as ‘syncope’ an old medical term meaning a sort of ‘fading away’ but most likely a heart attack or similar.

When James died, a few of the older Johnstone children had already left home to marry, enter service or work as agricultural labourers. However, Sarah was left with seven children under the age of twelve to care for and over the next few years, she moved several times to find work and somewhere for the family to live until, finally, all 13 children had left home.

All of the girls married local men and all three Johnstone sons joined up at the start of the First World War: eldest son Samuel was in the Royal North Devon Hussars; second son James also joined the Hussars and was eventually evacuated from Salonika incapacitated with malaria; and youngest son Thomas, in the Devonshire Regiment 5th Battalion, was killed in action on August 1917 during the opening phase of the Third Battle of Ypres near the Belgian village of Langemarck.

As an older woman, Sarah went to live with her youngest daughter Agnes and husband Reg Sedgebeer in Gunn, near Barnstaple and by 1939 she was living with her daughter Nora Thorne and son-in-law at Hawkscombe Cottage, Porlock. Sarah died in Porlock on the 11th July, 1945 in Porlock. She outlived five of her children, lost one son in WWI and two grandsons in WW2.

It is believed James is buried in Lynton cemetery and Sarah in Porlock but it is difficult to confirm. Some years ago the descendants of James Maxwell Johnstone placed a plaque in his memory in the cottage where he died.

The story of the Johnstone’s time at Hoar Oak Cottage must be viewed through the prism of the changing agricultural scene of the mid-1800s and the impact that had on the lives of the rural working-classes. As already described, both James and Sarah’s parents had travelled around Britain seeking work – Sarah’s father in quarrying; Jame’s in sheep farming. James and Sarah also moved about – from North Wales to Keswick to Scotland and then to Exmoor – constantly following agricultural work opportunities for James. The nearly 20 years at Hoar Oak Cottage must have been a period of stability for the couple . But it was a stability within changing times.

The ownership of The Exmoor Estate – previously the Royal Forest of Exmoor purchased by John Knight in 1818 – reverted to ownership by the Fortescue family of Castle Hill, North Devon in 1898. The Fortescues reduced the sheep farming operations put in place by the Knights and were ‘monetising’ their Exmoor properties by renting them out or using them for shooting parties – not using them as homes for tenants or employees. Consequently, many of the shepherd families, including those from Scotland, lost their jobs and homes on Exmoor.

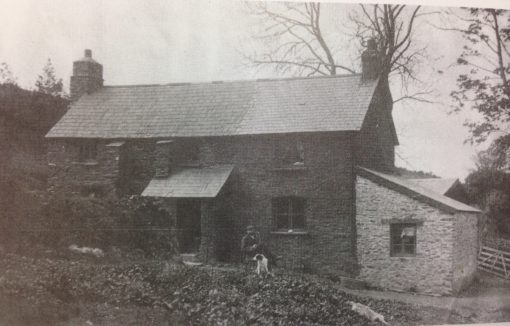

It is somewhat surprising, therefore, that in 1902, Viscount Ebrington, who later became the 4th Earl Fortescue, put in hand arrangements to extend the cottage in order to house the expanding Johnstone family. By 1903, when the photograph above left was taken, Hoar Oak Cottage had become a substantial farmhouse with two downstairs’ rooms, a kitchen/dairy, at least two bedrooms upstairs and substantial outbuildings. The lean-to on the side is remembered as being ‘the boys’ bedroom’ at this time – although later families remember it being used to house ‘piggy’. It is believed that around this time a spring was diverted into a pipe which led to the new porch inside of which was a hand pump and sink. Being able to pump water under the protection of the porch roof – rather than collect buckets of water from the spring or river – must have been a great boon although still prone to freezing up in winter. It could still be seen in 2011, photo above right.

The cooking and heating arrangements stayed the same however – an open fire and clome oven for baking was all there was for cooking and feeding and washing and warming the large Johnstone family. The sanitary arrangements also remained as the ‘bucket and chuckit’ method. Lighting was by candle and memories serve to remind us that candles made primarily from sheep’s tallow provide a very poor light as well as being smelly and producing lots of black smuts.

Despite this clear investment in Hoar Oak Cottage by the Fortescue Estate subsequent events hint that the Johnstones may have seen the writing on the wall for their future on Exmoor. In October 1903, James Johnstone headed north to visit his family in Keswick and then on to Lanarkshire, the aim we are told, was to investigate whether he should consider moving back ‘north’ with his wife and children. He returned to Exmoor and Hoar Oak just in time for Christmas and we will never know what his decision about moving was as he died 3 months later.

The challenges of being the widow of a poor rural shepherd would now descend upon Sarah in full force. A sheep farm is always in need of a shepherd – the sheep cannot be left to fend for themselves for very long – and landowners need to act swiftly when, as in this case, the shepherd for the Hoar Oak herding had died and the cottage was needed for his replacement. Sarah’s life and future prospects came to lie in the hands of two powerful agencies – the land owner and the local parish.

Records held in the Devon Record Office show that the Fortescue’s Land Agent, George Cobley Smyth-Richard, wrote an entry in his diary for 21st March 1904, five days after James’ death. It reads:

“I rode out to Hoar Oak and saw Mrs Johnstone on the loss of her husband and said I should like to see how her affairs stood.”

Cobley Smyth-Richard’s decision was that son Samuel Johnstone, by then 18, was thought old enough to keep the Hoar Oak herding going immediately after James died but was not considered old enough to take on the herding in his own right. The Land Agent visited Hoar Oak again on the 12th of April 1904. What he thought is not recorded in his diaries but within three weeks, just eight weeks after James’s death, Sarah and the younger children were gone from Hoar Oak Cottage and living in a cottage at Shilstone Farm, Brendon. Some of the Johnstone descendants remember that, when James died, Sarah was offered the chance to go back to Scotland with the younger children. Here another influential agency, the local parish, would be in action to affect Sarah’s life. Local parish support for a family like Sarah’s would, in 1904, involve supporting the widow and children to return to their ‘home’ parish and family. In Sarah’s case this would be Scotland, or perhaps Cumbria or even North Wales as her parents, too, moved about. She would not be supported to carry on living on Exmoor. (Note how a similar fate befell the Renwick family on https://hoaroakcottage.org/Renwick

Caught between a rock and a hard place, Sarah decided to stay put in Devon. And who can blame her. She already had married children and grandchildren living nearby whom she would not want to leave behind. Nor would she likely want to split her family up and take the younger children away north. The home she moved to in Shilstone, near Brendon is a small cottage but it was near enough to Brendon School that her school age children could, for the first time, be sent to school. Up until then the distance to travel across open moor to school from Hoar Oak Cottage was too far. The June 1904 Brendon School Registers find Johnstone children being enrolled – although one of the girls, Mary, was found to have consumption and was ‘sent home’.

After James’s death, Sarah seems to have had a few years of stability, albeit very impoverished stability, and family memories are that they were “hard times” that were “best forgotten” when Sarah “never had a penny off the parish.”

In 1913, Sarah moved into Lynton where she worked for many years as a cleaning lady in the Sinai Hotel. As an older woman, her family looked after her and she lived first with one daughter in Gunn and then later, with another daughter, in Porlock. She died in July, 1945. She had outlived five of her children. Her death certificate records her occupation as ‘Widow of James Maxwell Johnstone, Farm Shepherd’ – a fascinating insight into how, even 40 years after James’ death, Sarah’s life was still defined as a widow of a shepherd.

The chapter on Sarah Johnstone nee Thomason in “The Women of Hoar Oak Cottage – An Untold History” contains more details about this family and their life at Hoar Oak Cottage.

To get a copy go to:

- Books4Sale – hoaroak (hoaroakcottage.org)

- https://hoaroakcottage.org/books4sale/

- email: info@hoaroakcottage.org