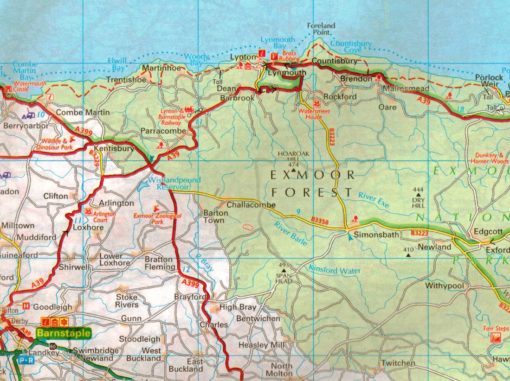

Hoar Oak Cottage is located in one of the most elevated and uninhabited parts of Exmoor in North Devon. It sits on the western flank of the Hoar Oak Water valley – a river which rises in the boggy high ground known as The Chains and flows north to meet the East Lyn River before continuing on to the sea at Lynmouth.

This link will take you to Google Map aerial view of the relevant part of Exmoor.

There has never been a track or road to the cottage only the ancient north-south trackway which runs past the cottage. Nor has there been modern services such as electricity, piped water, the telephone, a gas supply or links to a sewage system. The nearest farms, churches, schools and roads are several miles away and the nearest villages are Barbrook, Lynton, Brendon, Simonsbath, Challacombe and Parracombe. The nearest big town is Barnstaple. In 1873, a cottage hospital was built in Lynton – not a quick or easy journey in an emergency but no doubt a welcome addition to nearby facilities.

Even the delivery of the post was slow in coming to this remote spot. The first uniformed postmen started delivering in 1793 and postal orders were introduced in 1881. But it wasn’t until 1904 that Hoar Oak Cottage was finally included in the local, postal delivery service – and that was thanks to the intervention of Queen Victoria. The postman’s thoughts on the matter are, however, not recorded but we do know they asked for a pay rise! More on this link.

One of the most common questions asked about Hoar Oak Cottage is ‘how did people live in such a remote spot?’ and its impact on day to day life is described in more detail on these links: Work Life, Domestic Life, Growing Up, Community and Change. One key aspect of living in this remote spot is inevitably the weather and the affect it has on day to day life of both humans and sheep. The perils of snow were a constant threat in winter.

The light dusting in the photo above looks charming but prolonged cold, with heavy snow and the terrors of drifting snow, are both recorded and remembered. The diaries of Robert Tait Little (Head Shepherd from 1870 to 1907) describe, for example, the Great Snow Storm of 1878 and the challenges of getting the doctor or midwife out to a woman in childbirth or to a sick child, when the moor is deep in snow, are recalled by many Hoar Oak descendants. Self help was the order of the day. When Samuel Johnstone, as a child in 1900, fell off the roof of the lean-to of Hoar Oak Cottage and broke his leg he was carried down to the river to sit in the icy cold water until his shepherd father came home, pulled the broken bones into alignment and splinted the leg. Hot weather brought its own problems as well as pleasures and hardy though the shepherds and their families were, the trials of living in this remote spot – bad weather, farming problems, personal tragedies – sometimes brought irrevocable changes to peoples’ lives. You can read more on the links below.

Living at Hoar Oak called for a solid knowledge of, and respect for, the countryside as well as a well-tuned ability to get about in a landscape with so few tracks or easy markers to show the way. The amusing story of Shepherd Little and his intimate knowledge of the open moor around Hoar Oak is captured in Exmoor: Sporting and Otherwise (1948) by E J Marshall which tells how the Exmoor Hunt regretted ignoring Shepherd Little’s advice. More on this link.

Another much loved Exmoor author, Hope Bourne, writing in her book Living on Exmoor (1963) captures the remoteness of Hoar Oak Cottage in the years of it’s decline in a poignant and evocative way. Hope had been out walking on Exmoor and this story also involves The Hunt which Hope had been following across the moor that day. She writes:

Under the edge of the lowering hills, by the stream that runs down from its source in the great black bogs, by the purple shroud of heather, a roof and a gable jut from a knot of ragged beech and broken fencing lies in the bracken. The shepherd’s cot stands empty and deserted. The whitewash has turned grey and peels from the walls, and the door is set heedlessly ajar. Here and there the slates begin to slip from the roof. The windows are blank and sad. A raven sits on the chimney-pot and croaks, then bestirs himself to fly off at the approach of footsteps.

The enclosure that was once the little garden is ragged-hedged and broken-banked, and choked with nettles and odds and ends of abandoned rubbish. The small fields that once folded sheep and cattle are lapsing back to the moor, with only a hem of fallen wire to mark their difference, and the gates are fallen down. No one lives here now.

The cot, the little place with its sheds and smalls enclosures was once the ‘herding’ for many miles of wild desolate moorland on which were pastured big flocks of sheep, too far out for management by the established Forest farms. No road leads to it nor any track of discernible sort, and to make a road would be too costly in terms of modern economics. The moor surrounds it on all sides, a lapping tide, and only the ravens and foxes keep it company now. Some sheep there are still on the hill, wild Scottish Blackface, but they are strays from a farm far off down the valley.

I turn away sadly from the cot. It was a pleasant little homestead once. A small island of life and comfort in the waste, and often the orange glow from its windows must have lighted home the shepherd of the hills late about his task. There is always sadness in an empty and crumbling house where once there had been hearth and warmth and human hopes. Out of the very desolation of the poor little place I feel my own home call to me, and I quicken my steps away to be by my own fireside before the dusk falls fast about the empty hills.