Isolated and remote, Hoar Oak Cottage and its residents were not immune from change and one simple cause for change remained constant: it is there because of the sheep pastured in and around the Hoar Oak Valley. Hoar Oak Cottage is all about the sheep and the shepherd tending them needing somewhere to live. If something happened to the shepherd, whatever the reason, then another one had to be found quickly. If he died, or changed jobs, the family would have to move on immediately for the cottage would be needed for the new man and his family. Scattered throughout the story of Hoar Oak Cottage are the individual stories of change for the families – adapting to a new way of life or a new community, thriving, surviving, suffering and loss.

Changes involving land ownership and use had been taking place from Anglo Saxon times, if not before. They affected individuals’ commons right to use the moor for grazing animals, hunting and fishing and gathering natural products such as peat and bracken. After the Norman Conquest, the rules governing rights and access to the Royal Forest of Exmoor – when crown rights to hunt became more rigid and complex; they were stringently enforced for many hundreds of years.

Major change came when, in 1816, the Royal Forest was purchased by John Knight for £50,000. Over several decades, John Knight and his son Frederic began an ambitious plan to develop 16,000 acres of Exmoor by enclosing and reclaiming the moor, building roads, opening mines, building and populating numerous new farms with tenants and creating a community based around Simonsbath. Although Hoar Oak Cottage was never part of the purchase, much of the land forming the Hoar Oak Herding was and in time the cottage was leased by the Knights in order to house their shepherds working in the Hoar Oak Valley. Although many aspects of the Knights’ plans and development never came to fruition, the cottage at Hoar Oak continued its role for the next 150 years or so.

During the nineteenth century, industrialisation, population growth and the development of new markets in Britain as well as globally, all fuelled by the creation of a national transport infrastructure, combined to make their impact. Changes in agricultural practice with the need to increase production and the effects of competition were additional pressures on the price of meat and wool. Travel was easier and steam boats and trains brought new and different people to Exmoor – tourists as well as, for example, the Scottish shepherds who came to work on the moor. Increasingly, the inhabitants of Hoar Oak Cottage would be effected by national or global changes: the impact of a bad winter, market demands and fluctuations in prices for wool, meat and other products.

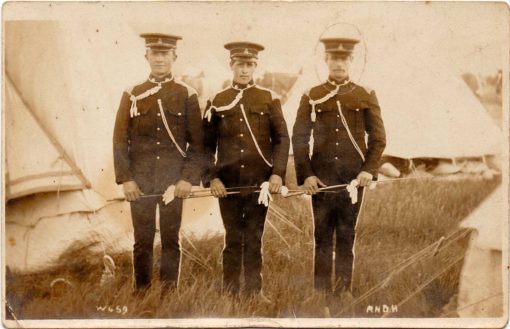

The two World Wars of the 20th Century had its impact, as it did elsewhere, on this quiet corner of Devon and inevitably on the shepherd families of Hoar Oak Cottage. Men left Exmoor and their farms behind. Some volunteered and some were conscripted. John Jones took on the Hoar Oak herding when his uncle Bill Hobbs volunteered and joined the North Devon Hussars. John’s role as Hoar Oak shepherd was a ‘starred occupation’ – a job important to the war effort. But in time, when the war was taking its toll and more and more men were needed, John Jones came up before a war tribunal in Lynton. His shepherd’s job was ‘unstarred’ and off he went to war. Three Hoar Oak brothers, James, Samuel and Thomas Johnstone all went to war – Thomas never to return. (More information to come.) Military impacts also changed the Exmoor landscape as many of the remotest farm cottages were destroyed – used by the Army for gunnery exercises and reduced to rubble in the process. Hoar Oak Cottage, which continued to be lived in until the 1950s, escaped this fate.

The growth of the nation’s interest in natural landscapes and disappearing environments during the 20th Century brought the next big change for Hoar Oak Cottage. The National Park movement began and Exmoor became one of the new designated National Park Authorities in the 1950s. Hoar Oak Cottage and the land around it became absorbed into the new park; the last occupants of Hoar Oak Cottage left and the cottage was left to fall into disrepair. Happily, the interest in the human story of Hoar Oak grew and the cottage clung onto its presence in the landscape. Now preserved as a stable heritage ruin, by the Exmoor National Park Authority through its Landscape Partnership, the cottage stands as proud testament to the hardy folk that have lived and worked in the remote Hoar Oak valley since time immemorial.