Between 1800 and 1940, at least 20 children were born at Hoar Oak Cottage. They led a hard but hardy life in this remote and untouched environment. Many were often cold and hungry and poorly shod and most were untroubled by too much formal schooling – but theirs was a wild and free childhood in a wild and free landscape. They lived like “little savages” one descendant remembered (Lethaby) but they were knowledgeable about the moor, were good with the sheep and ponies; and were able to care for dogs and chickens, pigs and ducks.

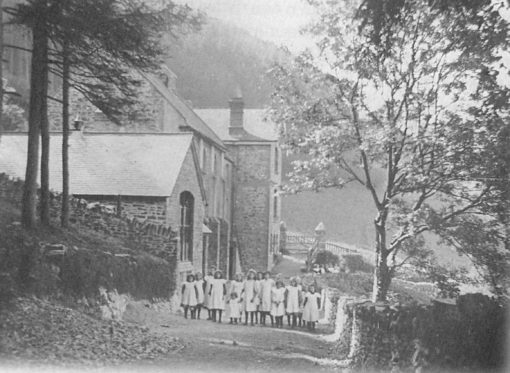

Archive Ref: 3394/HOC46

They were independent and competent children who, from an early age, helped their father with the sheep and their mother with the chores and by 12 or 13 years of age would often be away at work themselves, earning money to send home.

Watch one descendant, Jim Vellacott, talk about growing up on these links:

• Jim Vellacott talks about fetching herring from Lynmouth

• Jim Vellacott talks about checking the barometer for haymaking

And read more about how the children helped with domestic chores and the sheep on these links:

• Hoar Oak Talking Baking Day

• Hoar Oak Talking Washing Day

Strangers didn’t often come by Hoar Oak Cottage but when they did it could be a time for concern. The shepherd’s wife, on her own, in this remote spot with young children had to be cautious. Some descendants recall how the Hoar Oak mothers kept their children safe and secure in this lonely spot by telling them, when they saw a stranger approaching, to ‘get up the trees and hide.’ Children would quickly scramble into the beech trees at the back of the cottage whilst their mother saw the stranger on their way or made certain there was no danger to her brood. Learn more on this link .

Schooling could be something of a hit and miss affair until the 1900s, when there was a legal requirement for the children to go to school. Before that, home tutoring was the norm and there’s little doubt that some children received little education and probably struggled with reading and writing. Signatures on documents, such as marriage certificates, are often replaced by an individual’s mark ‘X’. However, some children received a good education through home tutoring as recalled by one descendant of the Scottish shepherds, “Grandfather was quite well educated, he taught the children and they all worked very hard so life was never dull.” (Stevens) and this home tutoring during the Scottish shepherd era even made the news. More to come. Children that did go to school travelled to the local village school on the family pony, staying with relatives during the week – variously attending Simonsbath, Barbrook and Brendon Schools (Antell, Little, Hobbs). The Barbrook school register provides interesting insights into the many reasons why these children from the far-flung moorland farms had poor attendance. We see that children were kept at home helping with lambing, with shearing, with digging potatoes, with planting potatoes, because of bad weather and far too often, because of illness. More on Exemption from School Attendance on this link

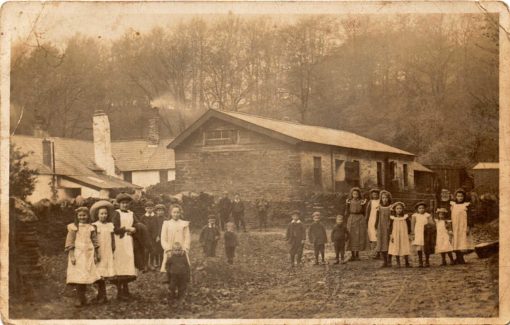

Archive REf: 3394/HOC264/1

Archive Ref: 3394/HOC163

The notion of healthy little Hoar Oak ‘savages’ recalled by one descendent didn’t, sadly, apply to all children. The Bale family lost both baby daughter and mother, within three weeks of each other in May 1844 and little Annie Renwick was just four months old, in 1883, when she died at Hoar Oak. Two of the Johnstone children were sent home from Brendon School in 1905 with tuberculosis – happily both recovered and lived to old age. Records show that respiratory and gastric infections as well as the more obscure condition described as ‘decline’ were often the cause of death. However, the Bass family lost three children to the effects of ‘poisoned milk’ in 1922 – just as public health awareness around sterilisation was rising. And in the 1940s, the Antells – the last shepherds at Hoar Oak – lost their first son Billy in 1938 to a viral infection which hospitalisation couldn’t save him from.

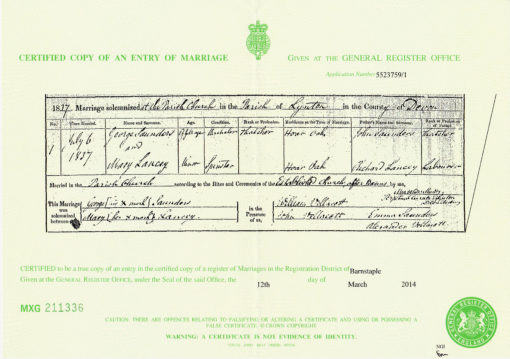

Mary Lancey, who grew up at Hoar Oak Cottage, not only survived and thrived but married her parents’ lodger – George Saunders from Dorset who was employed in the local area as a thatcher. A happy story with a bit of history attached as Mary and George were the first couple married in the Lynton area after the introduction, in July 1837, of the act which introduced birth, death and marriage certificates. Their certificate shown below, has No.1 proudly recorded in the certificate number column on the far left. More on this link.

Archive Ref: 3394/HOC125/1