Below are a series of blogs posted during the 2025 year of The Soldiers of Hoar Oak Cottage exhibition. They are additional, and sometimes more in-depth, pieces about the men featured in the publication The Soldiers of Hoar Oak Cottage but which didn’t make it into the book. Go to www.hoaroakcottage.org/books4sale where you’ll find details about how to buy a copy.

Frank Johnstone in Poland. Blog posted May 25th 2025.

Frank Johnstone was one of almost 10,000 Allied troops captured by the German Army in north-west France in mid-June 1940. His mother, Jane, was born at Hoar Oak Cottage where his grandparents, Sarah and James Johnstone lived and worked as shepherds. Frank’s war time story is told in The Soldiers of Hoar Oak Cottage publication and on this posting we fill in a few extra details about Frank’s extraordinary story.

Frank was in the 1st Field Regiment Royal Horse Artillery (1RHA) which was part of the 51st Highland Infantry Division. In mid-May 1940, 1 RHA had been ordered by Allied commanders to withdraw from the defensive positions they held in eastern France close to the German border and to move as swiftly as possible the 300 miles to the French coast to be evacuated by sea. As they approached the coast German armoured units cut-off their intended escape route preventing them from reaching the Dunkirk evacuation beaches. As a consequence, they were forced to head instead for the port of Le Havre where they were, once again, thwarted by the continued rapid advance of the Germans across this part of France.

In a desperate last ditch attempt to get away, the 51st Highlanders, including Frank, moved further south and west making for the small fishing port of St Valery-en-Caux where it was hoped they could be reached by the Royal Navy. However, this proved to be impossible due to the harbour’s restricted size and the surrounding shallow waters. After two weeks of defending themselves around St Valery – and by then short of ammunition, food and water – the 51st Highlander’s commanding officer elected to surrender rather than continue with a battle they could not win. It was 12th June 1940.

In the initial confusion following the evacuation through Dunkirk and other ports, Frank’s wife Despina as well as his mother Jane and grandmother Sarah would not have known that he was not amongst those who had managed to escape back to England. Initially Frank was reported by the Army as ‘missing’. This news was probably greeted back home on Exmoor with a mixture of concern and hope that he had survived.

Frank, now a prisoner of the Germans, was first transported to a POW camp in Dortmund, Germany. His stay there was short and through the remainder of 1940 and the first half of 1941 he was held in several different POW camps in German-occupied Poland. Conditions in these camps were poor and prisoners had to work in the surrounding area as forced labourers especially in agriculture, mining and industry to support the German war effort. Frank was held in the following POW Camps: Stammlager 6D in Dortmund, Germany; Stalag 21B Szubin nr Posnan in northern occupied Poland; Stalag 21C/Z Grodzisk Wielkopolske in central occupied Poland and finally in Stalag XXB (20B) Malbork a large POW Camp located close to the Polish town of Malbork around 35 miles south of the port of Gdansk on the Baltic Sea northern occupied Poland. Frank arrived at Stalag XXB in the summer of 1941 and worked there and in various satellite work camps linked to Stalag XXB.

Back in Coggeshall near Colchester in Essex – where Frank lived with his wife Despina and children – it is highly likely that by the time Frank was at Stalag XXB his wife Despina would have received formal notification from the War Office in London that Frank was a prisoner of the Germans. This information would have been given to the Red Cross by the German authorities but would not have included details of Frank’s exact whereabouts nor his physical condition

Through the second half of 1941 and into 1942, Stalag XXB was continuously expanded to accommodate more and more POWs particularly from eastern Europe in order to increase the availability of forced labour. Coupled with overcrowding, malnutrition and unsanitary conditions inevitably illnesses such as dysentery and pneumonia and diseases such as diphtheria and typhoid fever spread rapidly through the camp. It was Frank’s fate to be infected and with the lack of basic medical care he died in the camp. It was the 17th of August 1942 – two years after he was captured at St Valery in France.

A month after Frank died, Despina received Army Form B 104-82 dated 21st September 1942 home informing her of Frank’s death. The information on the form was stark. It stated that her husband Frank had ‘died whilst in enemy hands’ but provided no other details. A further three months passed before, in mid-December 1942, another official form was delivered to Despina. This time it was Form D.2. Dated 14th December 1942 it was a letter from the War Office signed on behalf of the Director General, Graves Registration in High Wycombe. Once again, the information given was stark – simply informing Despina that the Graves Registration had received information that Frank had been buried in Grave 163 in ‘Marienburg Cemetery in Germany.’ Most likely this would have been the first definite indication she had of where he had been held as a prisoner.

In fact, the information in the Graves Registration letter was not entirely accurate. Frank had not been buried in Germany as stated in the letter but in German-occupied Poland. The name Marienburg quoted in the letter was the name used by the occupying Germans for the town in Poland properly known as Malbork. Frank had actually been buried in the local Malbork Communal Cemetery. After the war was over the Imperial War Graves Commission (later renamed the Commonwealth War Graves Commission – CWGC) moved Frank’s remains from the Communal Cemetery and re-buried them in a marked grave in the nearby, newly created CWGC Malbork Commonwealth War Cemetery. In 2006 the Friends made a formal application to the Central Tracing Agency of the Red Cross in Geneva for Frank’s POW record. This information was sent to the Friends in a Red Cross Attestation dated 1st June 2006. It showed that Frank had, in fact, been held in five different POW camps during his two years of captivity along with the dates of each and confirmation of his death.

Frank is commemorated and remembered in 3 places – on his headstone in the CWGC Malbork Commonwealth War Cemetery in north-west Poland – Malbork Commonwealth War Cemetery | Cemetery Details | CWGC – on the Coggeshall War Memorial in Essex – Coggeshall – and on the Lynton War Memorial in his home town. Photos included show all of these memorial sites.

Edward Bowden in Thailand: Blog posted April 23rd, 2025

The story of Edward Bowden is, perhaps, one of the saddest in The Soldiers of Hoar Oak Cottage. His was not a ‘good war’. But nor was it easy for those left behind in North Devon – his widowed father, siblings and extended family. Here we share a little extra to add to his main story in The Soldiers of Hoar Oak Cottage available on Books4Sale – hoaroak

When, in January 1942, the surrender of the Allied forces in Singapore to the Imperial Japanese Army was reported on the radio and in the press, it is likely that Edward’s family would have initially been unaware that he was one of the thousands who were now in enemy hands. His deployment to Singapore with his signals unit had been kept a military secret. Later in 1942 the family would have been officially notified that Edward was listed as missing and presumed to be a prisoner-of-war.

Very little news of the fate of the captured men was heard or reported on over the subsequent months and years as the Japanese were in complete control of this part of south-east Asia – Singapore, Malaya, Thailand and Burma.

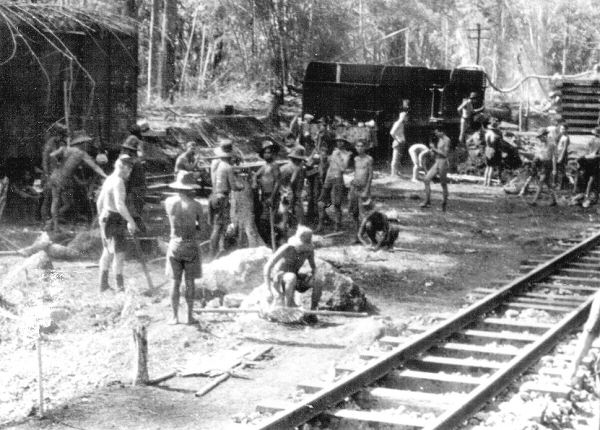

Edward was one of the many prisoners who were transported from Singapore to work as forced labour for the Japanese on the construction of the Thailand-Burma railway – years later it became infamous as the ‘Death Railway’. In Thailand where Edward ended up, as elsewhere, the men were subjected to brutal and harsh discipline, forced to work in inhuman conditions, were poorly fed, suffered from tropical diseases, injuries and the consequences of malnutrition all with little or no medical assistance available.

Information about the ‘Death Railway’ can be found on the webpage of the Thailand and Burma Railway Centre in Kanchanaburi: TBRC Online: BRIEF HISTORY

In a cruel twist of fate back at home, the North Devon Journal reported on the 22nd July 1943 that ‘after 17 months of suspense the Bowden family in Lynton had been officially informed that Edward was a prisoner of the Japanese’. No other details were provided by the authorities but no doubt this news would have provided his family with a degree of reassurance and hope that Edward was still alive. However, they had no idea that just a week after the family received this news, thousands of miles away in Thailand in a disease ridden Japanese work camp, Edward had been infected with the deadly disease of cholera during the severe cholera epidemic in mid-1943. Already suffering from dysentery, severe malnutrition and exhaustion coupled with the terrible conditions prevailing at the work camp Edward succumbed and died on 29th July 1943.

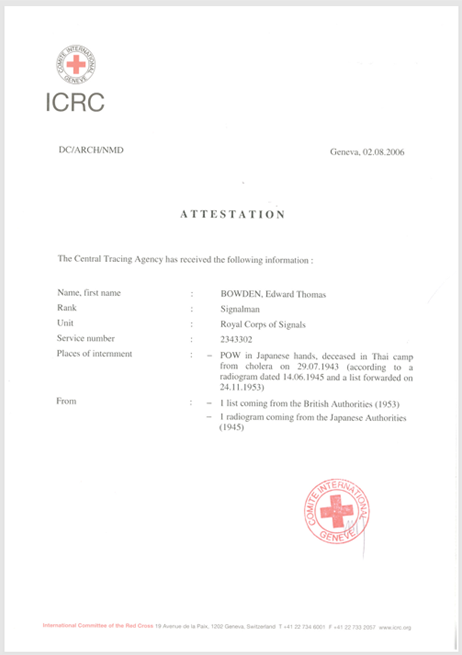

Another two years would pass before official notification of Edward’s death reached the British authorities via the Red Cross in a radiogram from the ‘Japanese Authorities’ dated 14th June 1945. Radiograms were a form of telegram transmitted by radio (wireless) used at the time to advise the status of POWs. It was only after this information had been received that Edward’s family were formally notified by the Army of his death. Nearly 10 years after Edward died as a POW his death was confirmed in a list ‘from the British Authorities’ dated 24th November 1953 and sent to the Red Cross in Geneva.

To understand more of Edward story, the Friends made a formal application in early 2006 to the Red Cross’s Central Tracing Agency in Geneva requesting a copy of his POW record. This was received on the 2nd of August 2006. It confirms that Edward died of cholera on 29th July 1943 whilst in Japanese hands in a Japanese work camp in Thailand. He was 23 years of age and such a long way from home.

Edward and other cholera victims had been hastily buried on the orders of the Japanese in pits outside the work camps along the railway route. Much later these men did finally receive a decent burial. Post-war, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission recovered their remains and buried them within the sanctuary of the CWGC war cemeteries at Chungkair and Kanchanaburi in Thailand. Edward was buried in an unmarked common grave at Kanchanaburi War Cemetery | Cemetery Details | CWGC. Now Edward is also remembered at the Commonwealth War Grave Commission’s Singapore Memorial located in Kranji a short distance outside Singapore City. Bette and Jim Baldwin of The Friends visited the Kranji cemetery in 2018 – Bette is Edward’s second cousin – and a memento was left in remembrance. You can visit the Singapore Memorial online at Kranji War Cemetery | Cemetery Details | CWGC and learn more about the Japanese Prisoners of War online at Changi Chapel and Museum

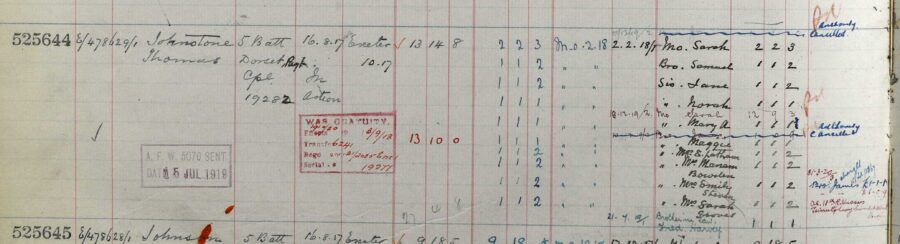

Thomas Johnstone : Pay & War Gratuity when killed on duty. Blog posted April 8th, 2025

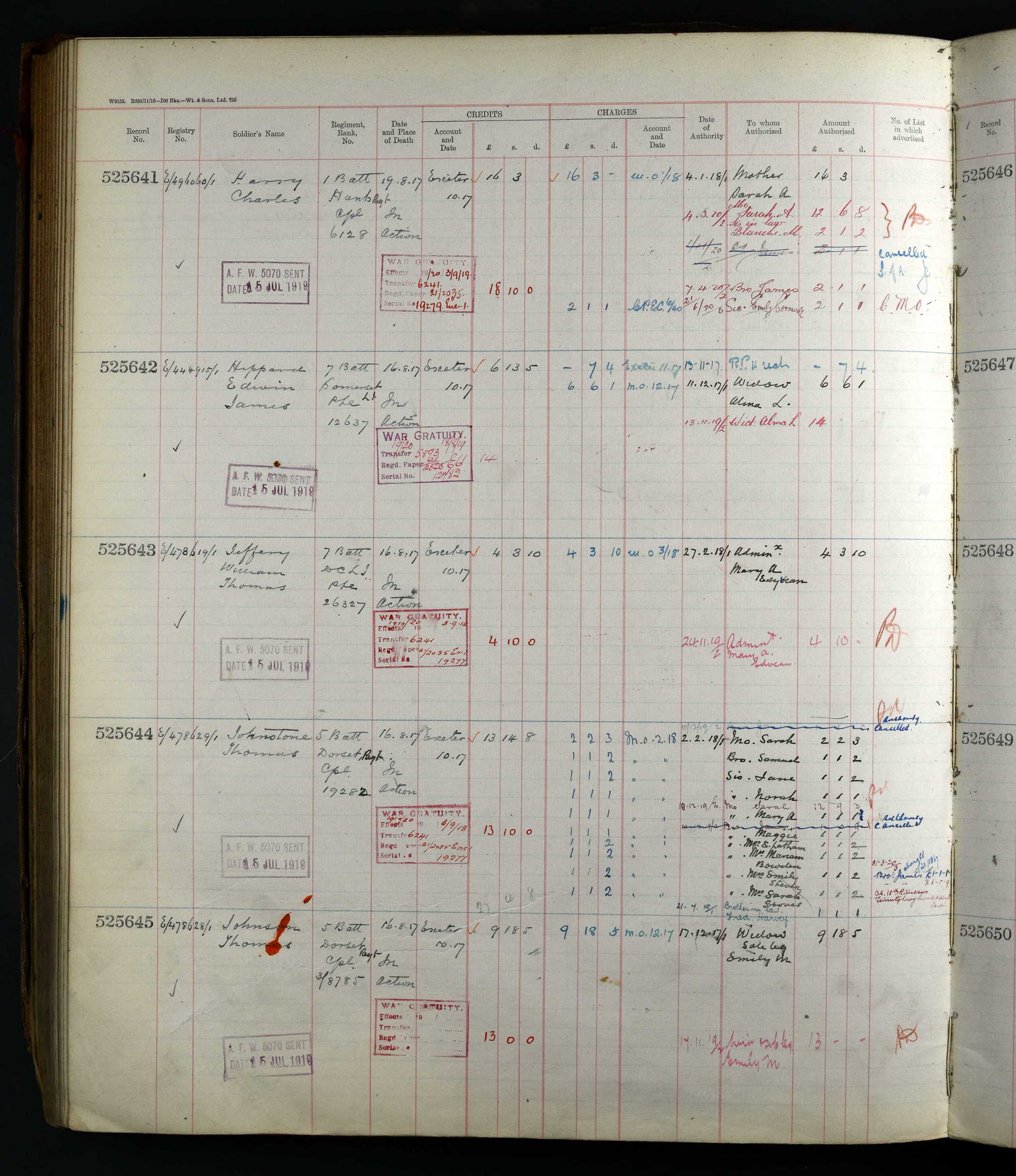

When a man was killed on active service his ‘legatees’ received his outstanding pay and a war gratuity. Somewhere deep in Army administration were clerks who were responsible for ensuring legatees received what was due them and recorded it all carefully in War Department ledgers. The contents of these ledgers are starkly factual as demonstrated by the column titles which include: Record No; Registry No; Soldiers Name; Regiment, Rank, No.; Date and Place of Death; Credits; Charges; Date of Authoirty; To whom authorised; Amount authorised. But the ledgers can also tell an interesting story about each man and the family he left back home. Thomas Johnstone, one of the young men featured in ‘The Soldiers of Hoar Oak Cottage’ can be found in just such a War Department Ledger. The page on which his name appears is shown below:

Before we get to Thomas’s story have a look at Record No. 525642 which shows that Edwin James Heppard, who died in action on the 16th August 1917, had 7s 4d (seven shillings and four pence) deducted from his salary before it was passed on to his ‘sole legatee’ his wife Alma. This deduction is most likely because he had been paid in advance, say a month in advance but died before the end of the month and was therefore ‘overpaid’ by 7s 4d. The remaining amount, minus the overpayment, was £6/6/1 – six pounds, six shillings and one pence and this went to Alma who also received a War Gratuity of £14. These gratuities were based on the soldier’s rank, length of service and time served overseas. So Alma received around £20 – equivalent to approximately £1000 today. It seems small compansation for the death of a husband but this was a reality which she and millions of other WW1 wives faced. We don’t know how many children, if any, they had but she would soon need to find another source of income in order to live. It is not surprising to find that many war widows are recorded as quickly remarrying. It looks a bit heartless but often it is more about sheer necessity.

Also have a look at Record No. 525645 which is, interestingly, for another Thomas Johnson. Not ‘our’ Thomas Johnstone with a ‘t’ and an ‘e’ but just like our Thomas he was also a Corporal in the 5th Battalion Dorsetshire Regiment and also died on 16th August 1917. Thomas’s widow Emily, was ‘sole legatee’ and received £9/18/5 in pay as well as the War Gratuity of £13. Why Emily received less as a widow than Alma may have been to do with the number of dependent children left. The records for Edwin & Alma Heppard and Thomas & Emily Johnson are both quite straightforward. The men were killed in action. Their wives received their husband’s salary (minus deductions if they applied) plus a War Gratuity for their widow status.

Turning to ‘our’ Thomas Johnstone’s of Hoar Oak Cottage record – Record No. 525644 – we find a rather more complex story of the task that the Army clerk had to disperse Thomas’s money to his legatees. Some readers may remember that Shepherd James Johnstone and his wife Sarah had 13 children at Hoar Oak Cottage. James died in 1904 and Sarah was left a widow with 7 or 8 of the children still at home. Her son, Thomas, had already left home but clearly didn’t want to forget any of his family when making arrangements for how his money should be disbursed if he was killed whilst serving his country.

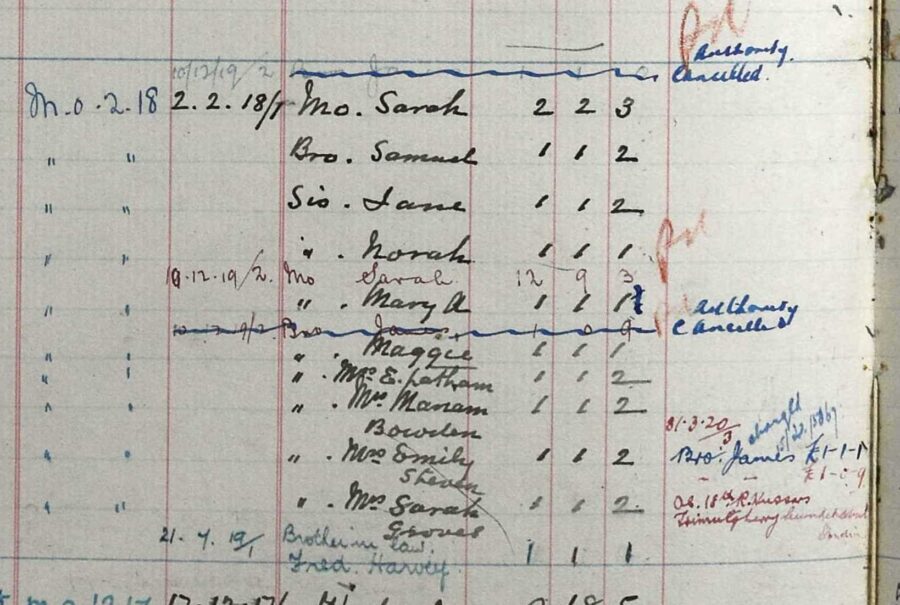

The record shows that Thomas had wages of £13/14/8d plus a War Gratuity of £13 making a total of £27/4/8d to disburse. Compared to the other entries in the ledger, the two close-ups of Thomas Johnstone’s entry (below) show it was a complex job for the War Office clerks.

Below is a transcript of Thomas’s disbursements, shown in the image above. Where the clerk has used different colour inks to denote comments and notes in the ledger, the same colours have been noted in the transcript below.

Bro(ther) James £1/1/0d Authority cancelled (blue) NB: Pd (red) added later

Mo(ther) Sarah £2/2/3d

Bro(ther) Samuel £1/1/2d

Sis(ter) Jane £1/1/2d

Sis(ter) Norah £1/1/1d

Mo(ther) Sarah £12/9/3d Pd NB: £13 War Gratuity minus 2/9d

Sis(ter) Mary A £1/1/1d

Bro(ther) James £1/0/9d Authority cancelled (blue) NB: Pd (red) added later

Sis(ter) Maggie £1/1/1d

Sis(ter) Mrs. E Latham £1/1/2d (married sister Ellen)

Sis(ter) Mrs. Marion Bowden £1/1/2d (married sister Marion)

Sis(ter) Mrs Emily Stevens £1/1/2d (married sister Emily)

Sis(ter) Mrs Sarah Groves £1/1/2d (married sister Sarah)

Brother in Law Fred Harvey £1/1/1d

It appears that Thomas’s Mother, Sarah, received the majority of the War Gratuity but it’s not stated where the other 10s 9d of the £13 gratuity went. Brother James is twice struck from Thomas’s disbursements list (Authority cancelled) but this is not to do with a lack of brotherly love and all to do with the difficulty for the clerk to track down Jame’s whereabouts. He was located serving in India and his money from Thomas ‘paid’. The note to the side of Thomas’s entry about his brother James says:

31/2/20 NB: this would be the date that the note, below in red, was added.

Bro(ther) James £1/0/9d

OS (Overseas)

18th R. Hussars (serving with the 18th (Queen Mary’s Own) Royal Hussars)

Trimulgherry, Sunderabad

NB: Trimulgherry is a suburb of Sunderabad in the state of Telengana in central southern India. Trimulgherry (today Tirumalagiri) was a well established British-Indian Army base.

It is charming to see that Thomas Johnstone left money to his two brothers, Samuel and James, whose own war stories can be found in the ‘Soldiers of Hoar Oak Cottage’ book. And that he left something to each of his sisters including newly married Ada who, unknown to Thomas, had also died aged only 29 shortly after his own death in Belgium. A later note added to Thomas’s disbursements by the authorities grants the £1/1/1d due to Ada to her widowed husband Fred Harvey.

This page from a simple Army accounts book can tell such stories. Not just about Thomas Johnstone of Hoar Oak Cottage but of the other men listed on ‘his’ page. It captures a group of men who all died on the same day during the same battle. It is very likely that Thomas knew the ‘other’ Thomas Johnson (the next one in the ledger but without the ‘t’ and ‘e’). They were both Corporals in the 5th Dorsets and would have both been deployed in the attack which took both of their lives against the heavily defended German held village of Langemarck – close to the besieged city of Ypres. This battle became known as the 3rd Battle of Ypres – often referred to simply as Passchendaele.

It also tells the story of the family and loved ones that these men left behind and the recompense they received for the loss of their husband/son/father. Did they think it was a meagre recompense? Who knows. Perhaps it was a very welcome, if small, sum of money to help them along at their own personal time of change and loss. As for Thomas Johnstone’s family. Well he didn’t seem to want to leave anyone out and one can imagine the family gathering at one of their home’s in and around Lynton and looking at their £1/1/2d or £1/1/1d and remembering their young brother with love and a laugh. In today’s money they’d have received approximately £60 each. What did Mum – Sarah – do with her War Gratuity money? In total is was £12/9/3 – approximately £750 in today’s money. Probably, like most mothers she gave it to her children and grandchildren and said something like, “You have it. I don’t need it.” Sarah kept a photo of Thomas in an oval frame surrounded by flowers – a lovely little memento – and The Friends have an image of it in the Archive.

If you would like to buy a copy of The Soldiers of Hoar Oak Cottage – just £5 + P&P go to Books4Sale – hoaroak to find details or email info@hoaroakcottage.org directly.