When the early shepherds travelled to Exmoor from Scotland with their sheep it was not surprising that they continued to use the traditional Scottish ways of caring for their flocks.

When the early shepherds travelled to Exmoor from Scotland with their sheep it was not surprising that they continued to use the traditional Scottish ways of caring for their flocks.

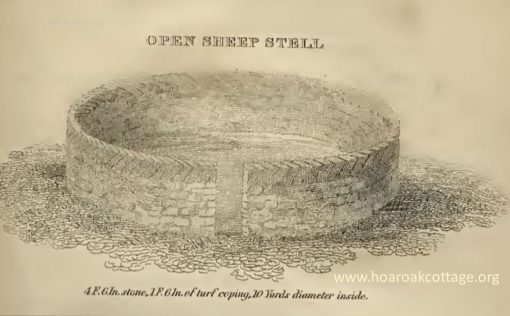

During the winter months’ a careful watch on the weather was essential for a sudden snowstorm could result in the loss of large numbers of sheep. If the snow came late in the season, the losses could be even greater for the ewes would be heavily pregnant. Even if they survived, the stresses the weather caused through cold, exhaustion and hunger would often result in the death of unborn lambs. One way to protect the sheep was to build stells – stone enclosures that the sheep could enter whenever bad weather was imminent.

Perhaps what is more surprising is that, although the shepherds are long gone, it is still possible to find traces of their methods both on the ground and through the notes they kept – for example in Head Shepherd Robert Tait Little’s diaries.

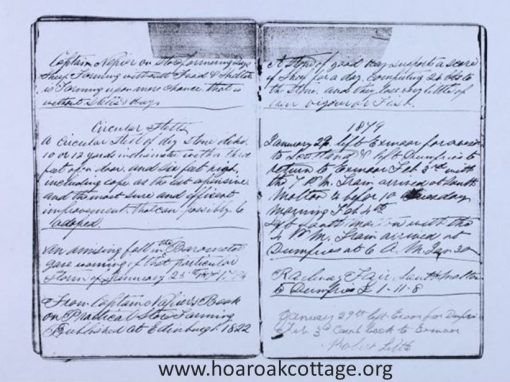

In his diary for 1879, he enters details of two visits to Scotland, travelling by railway to Dumfries from South Molton.

Alongside, he also makes detailed notes for the design of circular stells, quoting directly from the writings of Captain William Napier (published 1822) who farmed at Etterick:

“…a circular stell of dry stone dike, ten yards in diameter, with a three feet open door, and six feet high, including cope, as [sic] the least expensive, and the most sure and efficient improvement that can possibly be adopted…”

Just yards from Hoar Oak Cottage the remains of a such a stell is marked by low earthen banks. Bracken grows in the disturbed soil of the stell floor to form a perfect circle, making its position and size clearly visible.

Why circular? Although stells can be oval or even rectangular (as at Buscombe Beeches to the southeast of Hoar Oak), Captain Napier considers circular to be far superior: “…the action of the blast [wind] upon the circular surface of the wall, causes a rotatory motion in the air, to such a considerable height, that when the diameter of the circle is kept within proper bounds, the snow is thrown off at a tangent in every direction, and the included space left thus uncovered within…” He also states that it is not just he that is of this opinion but also of some others including, rather tantalizingly, a “Mr Little.” There is no way of knowing if he is referring to one of Robert Tait Little’s shepherding ancestors.

It is well established that sheep flocks that live and roam on unfenced mountain and moorland, learn through the generations to remain within a limited, albeit large, area of many hundreds of acres. They know where to forage and also where and when to take shelter. The shepherd, by building stells, takes advantage of this instinct for the sheep naturally enter and remain within the enclosure whenever bad weather is due. There is no need for a gate to retain them. Here, they are safe and can be kept well fed. Perhaps an even greater advantage of stells is that the shepherd is also safe for there is no need to be out on the moor searching for lost or buried sheep in drifting snow.

The photo below is an abstract from the landscape photo used by The Friends of Hoar Oak Cottage to show the cottage in its Exmoor setting. The Hoar Oak stell can be seen in the left foreground. The structure was probably built under Head Shepherd Little’s instructions when Shepherd Renwick o(1879 to 1886) or Shepherd Johnstone (1886 to 1904) were the shepherds in charge of the Hoar Oak herding.